[another cheese sandwich] [also, a kind of primal scene]

Of course, it wasn't anything like that, or even like that.

I had taken the Moscow sleeper to Helsinki. Embarked at Petersburg. I saw the sun rise from the train, as we rolled through a blasted landscape -- all the trees had been cut down -- punctured by the occasional long-abandoned monastery or, more frequently, clusters of tin-roofed shacks. I was in the top bunk. A couple slept below.

Here I am in Russia, I thought. This is Russia.

That's what it was, perhaps is, all about for me, that slight shift in point of view -- and the infinitely generative mistake contained within it. Here I am ... This is. And the moves that follow: Are you? You, really? And, where? Is it?

(There's a joke here, about dialects and dialectics. Not to mention dielectrics. Damned if I can find it, though.)

Anyway, to specify: I -- if it was "I", if one can say "I" -- was on my way to the border. At Vyborg, police would board the train. There'd be traffic in passports and visas. I had euros, rubles -- and a fistful of dollars, if it came to that. I wondered about the language in which the border transaction would occur. Last time, it had been in Russian. Mine had been passable, a thoroughly convertible currency, and I'd gotten some obscure extra cultural credit for speaking it. This time, I wasn't sure. (I am never sure, at these moments, if my language will be good enough, as if the currency on my tongue might be petrodollar or worthless paper or something in between, according to an exchange rate over which, strangely, I feel I have no control.) I stared at my passport, at the visa that had taken so much to procure. After days without documents in Petersburg, days in which I wondered whether my payment of a "passport tax" -- which the hotel had required, in American dollars, along with the surrender of my passport -- was actually going to be enough, I was just relieved to have the passport back. Not that I knew, in any significant way, who I was. Not that anything on my passport could tell me. Still, I could write my own name in Cyrillic. If it was mine. If it came to that. Would it come to that? How to tell?

I was on the border, and still making prison art.

Below me, the man and the woman woke slowly. She pulled her hair back into a ponytail and adjusted the pretty scarf at her neck. He shrugged into his coat. They were shy with each other, and oblivious of me. Are marriages the same the world over? They discussed her sister, his father, family matters, all the while speaking gently to one other, almost formally, as if courtesy were everything. Perhaps it is. When they finally noticed me, I spoke in haltingly in Russian, to show I had not understood what I'd overheard. This was important. A courtesy, also. But I'd screwed myself, in a way, because now I could not speak more fluent Russian to the border police.

I now wonder if this was not perhaps the most artful thing I'd done on the whole trip.

I had Osip Mandelstam on the brain. ... I am suddenly transitionless ... He died in a gulag, an imprisoned artist who managed somehow not to make prison art. A freedom he took, illicitly, and paid for - what currency - with his life. No dawn trains for him, no reliable velocity taking him across the border, out of the country. No dull, sweet conversation waking him up, either. Instead, just ambivalent wishing for a place in which to have a conversation of, I think, a different sort: We shall meet again in Petersburg, as though there we'd buried the sun, and for the first time, speak the word, the sacred meaningless one...

[for extra credit, tell me what's right and wrong, at once, about the title of this post. hint: prepositions of motion can be very hard to translate into russian]

20.10.08

17.10.08

Man on Wire

"To me it's so simple-- life should be lived on the edge of life. You have to exercise in rebellion. To refuse to taper yourself to rules, to refuse your own success, to refuse to repeat yourself. To see every day, every year, every idea as a true challenge and then you live your life on a tightrope." -- Philippe Petit, in Man On Wire

Dana Stevens' review of the film conveys both the irresistible beauty of le coup and, it must be said, the high personal cost of its success. After the WTC walk, Petit abandoned Annie Allix, his longtime lover and chief source of moral support, and J-F Blondeau, the childhood friend and secret sharer who came up with the ingenious idea of using a bow and arrow to send the wire across the void. While this idea solved a technical problem, its sheer homeliness may have also gone some way toward lowering the ambient anxiety, making the feat seem -- as I suspect it had to, for all of them, on some level -- like, despite the danger, it might still be just a prank, a lark, child's play.

I'm of two minds about whether the result was worth the sacrifice. Without the wound of 9/11, I might be inclined to say that while Petit's walk was beautiful, it was probably not worth the pain it caused, especially to Blondeau and Allix. One might object that they knew what they were getting into, or should have, and one would not be wrong. A small but necessary correction might be simply to give credit where it's due: everyone who helped Petit deserves gratitude, praise, admiration, not just Petit himself.

But there's more to it than that. It would be intellectually dishonest to fail to acknowledge that, after 9/11, Petit's walk seems like a profound gift.

I'm on a wire myself, writing this -- Petit's walk was certainly full of beauty, yes, but it was also a rebellion, full of rage and defiance. Crossing empty air, he was making his way through scary, primitive territory. If he'd fallen, would it have been "for us"? (For "our own good"?) The religious implications are clear enough; and no man should be a religion; one would hope that 9/11 alone would once and for all put the lie to messianism. Petit's walk seems questionable for just these reasons - it is easy to imagine how it could be put to a terrible use, as a justification for terror. But this would pervert it. There's an important difference between symbolic engagement with wild energies, and their mobilization in the service of terrible aggression in the real. The difference must be understood, and upheld - if only in defense of a world, now lost, where the incredible hubris of building two enormous towers on the south tip of Manhattan could be convincingly addressed (not bested, certainly not redeemed) by a daring man and a handful of no less daring accomplices, with no loss of life and, arguably, an increase of it.

So maybe the question becomes: Was the address convincing? Did Petit's act carry conviction? Or was it just a stunt?

As far as I know, Petit asked for nothing from his audience, not even their attention - he just stepped out into the sky. (It was Allix, from the ground, who cried, "Regardez!") He demanded no money, no press, not even the attachment of his name to the work. In this sense, at least, it was a kind of gift -- even before 9/11. At the same time, the gift still isn't unalloyed. I mean, why choose the towers, if not in acknowledgment of how wonderfully they would serve as a vehicle for his immortality, should he survive the crossing?

My friend, the poet Richard Katrovas, writing on prison art, has thoughfully pressed the same question even further, exploring the difference between art without conviction and the sorts of art that can get you, well, convicted. (Do the latter have more claim to our attention? More purchase on the truth? Is this linguistic register even useful? Claims and purchase -- this is the idiom of property.) Anyway, the essay I've just linked to is nominally about art programs for the incarcerated but more deeply about the problems posed by defiant art, including whether such art is even possible under the conditions of late (very late) capitalism. A witness to the Velvet Revolution, the son of a chronically incarcerated con man, and no stranger himself to real and symbolic imprisonment, Katrovas suggests that, especially in a so-called "free" society, the deepest freedom comes through the artist's embrace of ephemerality, the renunciation of the ambition to use art to build monuments to the self. Instead, there is the production of gifts, in Lewis Hyde's sense, best of all coming without a name attached:

Most art is prison art, if William Blake's famous 'mind-forg'd manacles' are taken seriously as endemic to the human condition. The truly free man or woman doesn't make art the way any 'serious' artist does, because any serious artist, any constant (in both senses of the word) maker of Small Art, does so because she or he is chained to compulsions and egocentric ambitions no less securely than the prison laborer or slave is chained to his Big Art task. Perhaps only when the work of art is conceived not as a commodity or monument or testimony, or prophecy or admonition, but as a gift, a true gift, does the artist, the giver, achieve something we may call freedom, though the product of such freedom certainly will not have purchase on 'greatness,' 'profundity,' 'wisdom'; such art will certainly be ephemeral.

(Which is not to say artists should not be paid for their work - but that is a subject for another day.)

* It now seems perfectly inevitable that I should be reading the late novelist Rocco Carbone's Libera i miei nemici, his last novel before his cruelly untimely death this summer, based on his work in the Rebibbia women's prison.

Labels:

commonplace book

,

lingua franca

,

most art is prison art

,

writing

16.10.08

On Being At Sea & Sort of Liking It.

[Cheese sandwich warning]

Richard Hughes' A High Wind in Jamaica, Angela Carter's Burning Your Boats, and Nicholas Christopher's Crossing the Equator top my list of "desert island" books, which I keep in the increasingly wistful and distant but persistent hope that someday I may wind up on just such an island, with just such a library.

Do you see me, atop the rigging, with my sunburned nose in a book? Look, I am waving at you - with my bookmark! Which I made myself, of seagull feathers and hemp and a blue ribbon I might have won sometime, or maybe stolen from the sky.

It is the color of my mother's eyes.

I love adventure stories. They always seem to involve an element of getting back to basics, back to the sea and sky, wind and water. Back to the elemental.

Once, when I was really, or more accurately, metaphorically, at sea, I went to the library, where I always go to get my bearings, and discovered the subject for my graduate thesis. Which started, naturally enough, in a navigation problem: the earth's magnetic field is weak but pervasive. It screws up compasses, makes navigation difficult under cloudy conditions. Someone in the megalomaniacal years of the early nineteenth century decided it would be a good idea to make global observations of this force, over long periods of time, in order to arrive at a method for figuring out what the strength of the field might be anywhere, at any time. Compasses could be corrected by book and algorithm. Sea adventures might yet require the library.

Well.

In the megalomaniaical years of writing my dissertation -- some might recall the party we threw when I finished, how we gave the -e-vite the opening line: Ladies and gentlemen, our long national nightmare is over -- I took a class, taught by my eventual dissertation advisor, on the history of ancient science and its influences on the early moderns, emphasis on Galileo and Newton. Astronomy, physics, mechanics -- I was in my element and out of my depth. (Both clichés are pleasingly exact, like the sciences in question.) For the first session, we were assigned all of Aristotle except the Poetics, which was a pity, given what was about to transpire. Five of us showed up for the first class, I think, including the professor. Class was held in his office. We wedged ourselves around a tiny table as he approached the whiteboard, where he wrote:

Fire. Water. Air. Earth.

"What are these?"

I had been reading Aristotle for days. I had been at sea for weeks. This was a graduate seminar. Surely, the professor could not be starting with Aristotle's doctrine of the elements? It was, if you'll forgive the pun, entirely too elementary.

We sat there, waiting to see who would jump, who would answer first. Perhaps it was a trick question.

"Come on, people," he said. He was getting exasperated. I couldn't blame him. He was all by himself up there, with all of us gawping at him, in confusion and awe and also not a little desperation. "What are these?"

Silence. Back to basics, I thought.

"Nouns," I said. "They are nouns."

Splash! In the laughter that followed, I realized that although we still didn't know where we were going, we had begun.

Richard Hughes' A High Wind in Jamaica, Angela Carter's Burning Your Boats, and Nicholas Christopher's Crossing the Equator top my list of "desert island" books, which I keep in the increasingly wistful and distant but persistent hope that someday I may wind up on just such an island, with just such a library.

Do you see me, atop the rigging, with my sunburned nose in a book? Look, I am waving at you - with my bookmark! Which I made myself, of seagull feathers and hemp and a blue ribbon I might have won sometime, or maybe stolen from the sky.

It is the color of my mother's eyes.

I love adventure stories. They always seem to involve an element of getting back to basics, back to the sea and sky, wind and water. Back to the elemental.

Once, when I was really, or more accurately, metaphorically, at sea, I went to the library, where I always go to get my bearings, and discovered the subject for my graduate thesis. Which started, naturally enough, in a navigation problem: the earth's magnetic field is weak but pervasive. It screws up compasses, makes navigation difficult under cloudy conditions. Someone in the megalomaniacal years of the early nineteenth century decided it would be a good idea to make global observations of this force, over long periods of time, in order to arrive at a method for figuring out what the strength of the field might be anywhere, at any time. Compasses could be corrected by book and algorithm. Sea adventures might yet require the library.

Well.

In the megalomaniaical years of writing my dissertation -- some might recall the party we threw when I finished, how we gave the -e-vite the opening line: Ladies and gentlemen, our long national nightmare is over -- I took a class, taught by my eventual dissertation advisor, on the history of ancient science and its influences on the early moderns, emphasis on Galileo and Newton. Astronomy, physics, mechanics -- I was in my element and out of my depth. (Both clichés are pleasingly exact, like the sciences in question.) For the first session, we were assigned all of Aristotle except the Poetics, which was a pity, given what was about to transpire. Five of us showed up for the first class, I think, including the professor. Class was held in his office. We wedged ourselves around a tiny table as he approached the whiteboard, where he wrote:

Fire. Water. Air. Earth.

"What are these?"

I had been reading Aristotle for days. I had been at sea for weeks. This was a graduate seminar. Surely, the professor could not be starting with Aristotle's doctrine of the elements? It was, if you'll forgive the pun, entirely too elementary.

We sat there, waiting to see who would jump, who would answer first. Perhaps it was a trick question.

"Come on, people," he said. He was getting exasperated. I couldn't blame him. He was all by himself up there, with all of us gawping at him, in confusion and awe and also not a little desperation. "What are these?"

Silence. Back to basics, I thought.

"Nouns," I said. "They are nouns."

Splash! In the laughter that followed, I realized that although we still didn't know where we were going, we had begun.

Labels:

entirely too much vanity

,

history of science

,

miscellaneous

14.10.08

Say, Human. Warious.

A fragment from Our Mutual Friend, in which Mr. Venus, Dickens' grim shopkeeper-emanation of the the grim Victorian unconscious, describes the wares he has on offer:

Tools. Bones, warious. Skulls, warious. Preserved Indian baby. African ditto. Bottled preparations, warious. Everything within reach of your hand, in good preservations. The mouldy ones a-top. What's in these hampers over them again, I don't quite remember. Say, human, warious. Cats. Articulated English baby. Dogs. Ducks. Glass eyes, warious. Mummified bird. Dried cuticle, warious.

His beloved refuses him, in her own handwriting: "I do not wish to regard myself, nor yet to be regarded, in that boney light."

Tools. Bones, warious. Skulls, warious. Preserved Indian baby. African ditto. Bottled preparations, warious. Everything within reach of your hand, in good preservations. The mouldy ones a-top. What's in these hampers over them again, I don't quite remember. Say, human, warious. Cats. Articulated English baby. Dogs. Ducks. Glass eyes, warious. Mummified bird. Dried cuticle, warious.

His beloved refuses him, in her own handwriting: "I do not wish to regard myself, nor yet to be regarded, in that boney light."

12.10.08

Comforting

In today's post, which is good all the way down, Mark closes with some comforting words on tough times:

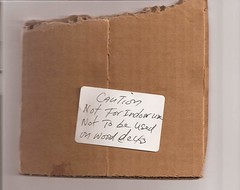

It may be that we're in for some rain. It's not our fault, and it's not our doing. Until the sun comes out, we can work indoors: write books, write software. Or we can go outside and get wet; that's fine, too. We're strong and young, the water will do us no harm, we can always find ourselves a dry towel and a hearth and we can be sure of dinner.

Gonna re-read that, first thing tomorrow.

It may be that we're in for some rain. It's not our fault, and it's not our doing. Until the sun comes out, we can work indoors: write books, write software. Or we can go outside and get wet; that's fine, too. We're strong and young, the water will do us no harm, we can always find ourselves a dry towel and a hearth and we can be sure of dinner.

Gonna re-read that, first thing tomorrow.

6.10.08

The Short Story's Napoleon Complex

Steven Millhauser has a wonderful essay on "The Ambition of the Short Story" in today's NYT.

The short story concentrates on its grain of sand, in the fierce belief that there — right there, in the palm of its hand — lies the universe. It seeks to know that grain of sand the way a lover seeks to know the face of the beloved. It looks for the moment when the grain of sand reveals its true nature. In that moment of mystic expansion, when the macrocosmic flower bursts from the microcosmic seed, the short story feels its power. It becomes bigger than itself. It becomes bigger than the novel. It becomes as big as the universe.

The short story concentrates on its grain of sand, in the fierce belief that there — right there, in the palm of its hand — lies the universe. It seeks to know that grain of sand the way a lover seeks to know the face of the beloved. It looks for the moment when the grain of sand reveals its true nature. In that moment of mystic expansion, when the macrocosmic flower bursts from the microcosmic seed, the short story feels its power. It becomes bigger than itself. It becomes bigger than the novel. It becomes as big as the universe.

Labels:

commonplace book

,

writing

3.10.08

1.10.08

SAR Arrives!

Not only does my new short story, "Eleven, The Spelunker" appear in the new issue of The Saint Ann's Review, but the SAR has very generously made the story available in its entirety online.

This is a heck of an issue, with ELEVEN (!) new pieces of short fiction -- a bonanza according to current literary periodical standards -- plus a slew of breathtaking poems, including a translation of "Ghosts of the Palace of Blue Tiles" by Jorge Fernandez Grenados, and art by Phillis Ideal, Tina Eisenbeis, Maggie Tobin and Jayne Holsinger.

All this, for just eight bucks - a feast. Subscribe.

This is a heck of an issue, with ELEVEN (!) new pieces of short fiction -- a bonanza according to current literary periodical standards -- plus a slew of breathtaking poems, including a translation of "Ghosts of the Palace of Blue Tiles" by Jorge Fernandez Grenados, and art by Phillis Ideal, Tina Eisenbeis, Maggie Tobin and Jayne Holsinger.

All this, for just eight bucks - a feast. Subscribe.

Subscribe to:

Comments

(

Atom

)